My Blog

Tache, Color, and Darkness November 3, 2024 15:49 2 Comments

I've been working on this traditional landscape, still in progress. I started out using a very watercolor type painting style, brushing across the support, not really being that opaque, and I was mixing watercolor paints like WN French Ultramarine with WN Permanent Yellow Deep Gouache. It didn't work. I had to redo it. I'm having to retrain myself to not use watercolor painting techniques with gouache.

I admire the flat, “poster” style of some gouache painting, but I don't want to do it myself. I want a little texture. At the same time, I don't really want to learn how to paint using gouache with a palette knife or even very thick paint that shows the brush bristles. I had thought that I did having seen R.K. Blades's gouache paintings where he uses texture and (I think) a palette knife or at least a boar bristle brush. But I want the paint to be more manipulable than that.

I decided to redo the background I had of this work, keeping in mind using gouache's qualities. Since it's not oil, I can't just paint over it like it's dry oil paint. I have to approach it with a soft touch if I'm covering a lot. One way to do that is to use tache. I'm not using it much like 19th-century artists did, for “optical mixing”--putting different colors close to each other counting on the human eye to mix them. I have never thought that kind of mixing actually works. The dots of different paint always stand out to me. But tapping the brush on the support can give a really nice variety of color due to the different thicknesses of paint, even if it's opaque. I think you can see that here, especially in the upper 2/3s of the painting.

I knew I could use a deerfoot brush to do that—I have regularly used my deerfoot brush to make leafy trees in watercolor (the deerfoot is the lower of these two; the other one is a blender). And then I can go ahead and scrub over them without having to worry about wrecking the lower level of paint. That's what I did with this. And I think that is working.

The other oil technique I can use with gouache is glazing/scumbling. I already knew that from other water-media paintings I've done where I've used scumbling, like drybrush watercolor. You use a dry brush and paint that's pretty thick on the tips of the brush hairs, paint that's a little thicker than heavy cream, and scrub. Then you can get a nice scumble layer, and it looks really good. It's kind of almost a hammered look, or like those small clouds one sometimes sees high in the sky, little cushions of cirrus clouds.

I do feel like I have a lot to learn about using gouache the way I want to instead of just trying to make it do what watercolor does. It can't do that. Or if I try to make it do that, it won't look as good as it would if it was watercolor. That would be just ignoring the inherent property of gouache—its opacity.

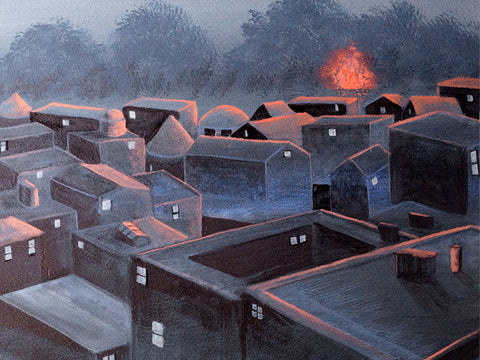

And I also want to work harder on having intense colors as opposed to the kind of gloomy colors I've been using. I like gloomy, but I think my paintings are not gloomy enough. They are too half-assed in terms of color. The one painting I did of the city with the sun coming up,

that was gloomy enough, but it could still be more gloomy than that. But with a lot of others, it's more like the colors are kind of tepid. They're not gloomy enough. So my paintings either need to be much darker, like the guy who painted those tree paintings where you just barely see the trees, it's night, or figures are just silhouettes.

The other side of that is using more intense color. I use lamps that are pretty bright so that I can see when painting small details. But that means the paint looks much brighter than it is in normal room light. And I end up with paintings that are limp in terms of color. I want to ramp up my color, make it richer and brighter.

So a couple of things I need to work on are continuing to explore tache as a painting technique and experimenting with more intense colors or much, much darker ones.

Aquapasto II August 27, 2021 20:19 3 Comments

Back in early 2018, I wrote a blog post about aquapasto. It's been my most popular blog post. People still come to read it.

I hadn't done much with aquapasto until recently, when I began experimenting with it again.

I first tried adding some to some paint to see if I could get lines to stand up. That didn't work.

I thought maybe I didn't add enough. Thing is that I noticed the more I added, the less brilliance the paint had--because, of course, there was less pigment per inch. It was spread out. What to do? Layers.

So I thought maybe it might be usable as some kind of transparent glaze, and I added much more aquapasto to each glob of paint, so that they were 50/50. I mixed them up with a very small palette knife I use with my watercolors, usually just to mix some tube paint with a bit of water and end up with something creamy. After mixing the paint and aquapasto, I added one spray of water so it wasn't so sticky.

For most of this painting, I used a type of brush I discovered through oil painting. It's usually used for painting grasses in landscapes and is called a grainer. It doesn't work that well for painting grass, but it's really interesting for building up texture. They are pretty cheap, but you could just as easily use an old flat brush in bad condition that's gotten splayed.

For most of this painting, I used a type of brush I discovered through oil painting. It's usually used for painting grasses in landscapes and is called a grainer. It doesn't work that well for painting grass, but it's really interesting for building up texture. They are pretty cheap, but you could just as easily use an old flat brush in bad condition that's gotten splayed.

I've experimented on and off with using watercolor paint almost straight from the tube to do drybrush work. This is the kind of painting that leaves a thick (for watercolor) layer of paint on the support, rather than the kind of scratchy drybrush you often see used for depicting Western or desert scenes--at least, that's what I associate that type of drybrush with. The kind of drybrush that leaves a thick, brilliant layer that never has the chance to sink into the paper and thus dilute its brilliance by coloring paper fibers below the surface is very rarely done, from my experience. One thing that seems to prevent watercolorists is the expense of the paint. But you really don't need to use that much, in my experience.

Drybrush does allow for glazing if you really careful to have very little water on the brush, use brights instead of rounds (which tend to dig up the lower layer of any kind of paint), and hold the brush at an angle quite close to the surface of the support, so you are basically skimming along. Adding aquapasto to the mix means not only can you do a drybrush glaze more easily, but you can build multiple layers and you can create texture that is unobtainable any other way.

You can see how thick the buildup of paint and aquapasto is here--thick enough to fill the dips in the canvas weave. This has about 7 layers of paint/aquapasto to it. It will seem even more filled when I finish the painting with cold wax, which I have been doing for the past couple of years. This will make it very water-resistant (I have tested it with a kitchen sink sprayer--beads right up). The painting can then be hung not only without glass but without a frame. If you do use cold wax, you might have to call it mixed media if you enter shows. But if you don't use cold wax and only the aquapasto, you are still allowed to call it watercolor, no matter how much texture you achieve with it, because aquapasto is a gel made from water, gum arabic, and some fumed (safe) silica and has been used by watercolorists for more than a century.

You can see how thick the buildup of paint and aquapasto is here--thick enough to fill the dips in the canvas weave. This has about 7 layers of paint/aquapasto to it. It will seem even more filled when I finish the painting with cold wax, which I have been doing for the past couple of years. This will make it very water-resistant (I have tested it with a kitchen sink sprayer--beads right up). The painting can then be hung not only without glass but without a frame. If you do use cold wax, you might have to call it mixed media if you enter shows. But if you don't use cold wax and only the aquapasto, you are still allowed to call it watercolor, no matter how much texture you achieve with it, because aquapasto is a gel made from water, gum arabic, and some fumed (safe) silica and has been used by watercolorists for more than a century.

When I first tried aquapasto back in 2018 and posted about my experiences on a now mostly defunct art forum, I thught other painters would be glad to hear how you could add texture to watercolor. Not so much. And worse, another poster scolded me for not sticking to "real" watercolor. Why didn't I just use acrylics or something, they asked with a sniff, the implication being that then the "real" watercolorists wouldn't have to deal with misfits such as myself.

Thing is I wanted to paint with watercolor, but I wanted to push the envelope, to see how much it could actually do. And what's more, aquapasto was invented by 19th-century British watercolorists, and you don't get much more "real" watercolorists than them.

So give it a try. Play with it and see what it can do for you. We need more misfits in the art world.